An Urban Village

01- Constructions

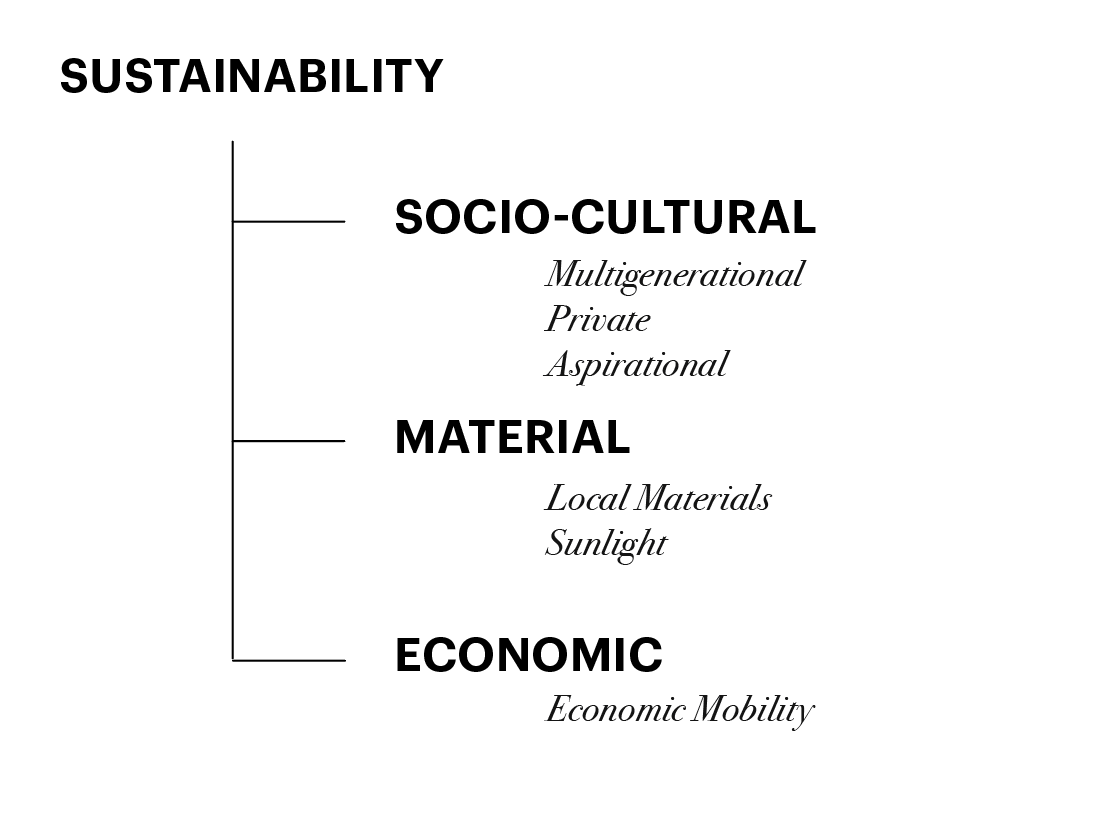

This thesis explores the role of Algerian domesticity in the creation of culturally, socially, and environmentally resonant spaces. By critically engaging with the legacy of French colonial housing projects, it aims to confront colonial design practices that often disregarded the cultural and social needs of Algerian domestic life. The design research seeks to integrate indigenous architectural principles, ensuring that the built environment accommodates both historical practices and contemporary needs. Central to this approach is the creation of sustainable living environments that prioritize social well-being and cultural continuity. The project challenges the modernist emphasis on efficiency, advocating instead for housing that fosters community interaction, supports the diverse roles within Algerian families, and promotes a sense of belonging. Ultimately, this project strives to offer an architecture that not only resists colonial legacies but also actively contributes to the reintegration of cultural heritage into modern Algerian life.

Academic Individual Project: Thesis

Date: 04.20.25

Advisor: Faysal Tabarrah

Softwares: Rhino, CAD , Illustrator, Photoshop

“ By piecing together elements drawn from personal recollections, family photographs, and oral histories, I can reassert the presence of labor, care, and communal bonds that Orientalist art erased. ”

“ Collage, in this context, becomes a medium for reclamation — an instrument to refuse static realism and, instead, highlight the adaptive intelligence that defined Algerian domestic life before and during the colonial period. ”

02- Provocations

Site Location: Bab El Oued, Algiers

In this proposed scenario, low-income families currently living in cramped apartments would receive individual plots of roughly 600 square meters. Although seemingly contradictory to urban density norms, this proposal emphasizes quality over quantity, challenging housing models disconnected from daily life. The chosen plot size of 600 square meters addresses practical and cultural factors: research highlights that a courtyard of approximately 6 by 10 meters significantly improves thermal comfort and energy efficiency. Surrounding this courtyard with residential spaces five meters deep results in a base dwelling footprint of about 320 square meters. Given Algeria's multigenerational family structure, the larger plot size accommodates future expansions, either horizontally or vertically, to house elderly parents, married children, or extended family, while also supporting home-based businesses or workshops.

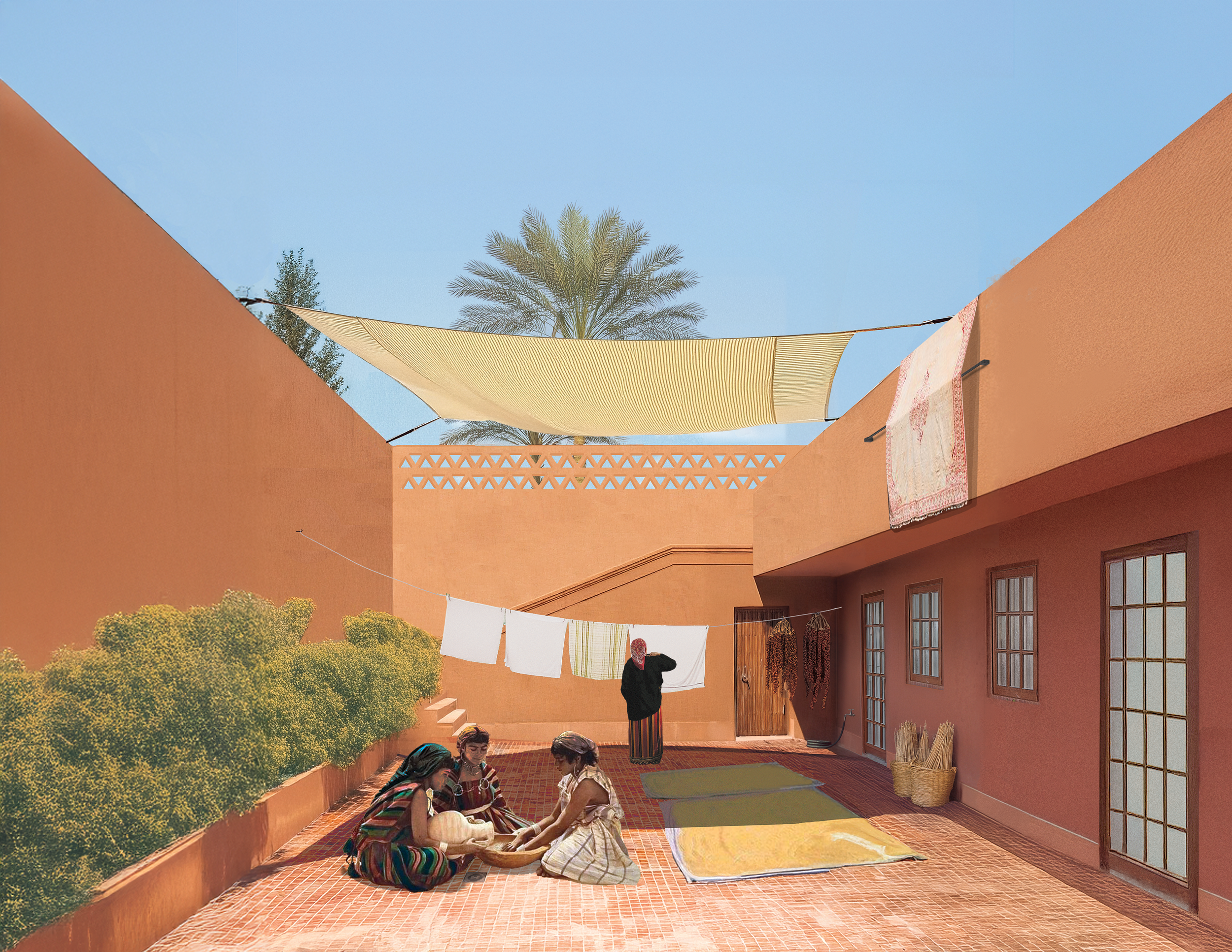

Like traditional Algerian examples, these courtyards offer climatic comfort, privacy, and communal space for daily activities. Local materials like mud brick, earthen walls, and lime renders further enhance thermal efficiency, reducing dependence on mechanical systems.

This design inherently supports phased expansion. Families can initially build modestly around their courtyard, confident in their ability to expand as needs arise. Regulations ensure expansions respect neighboring plots, mandating inward-facing windows and height limits to preserve privacy, sunlight access, and cultural practices, particularly women's privacy in domestic spaces.

At the Houma Scale

The first set of three isometric views offers a longitudinal perspective, depicting the slow accretion of family needs and cultural expression over time. In the earliest stage, each parcel holds little more than its base courtyard and a few essential rooms, an almost austere starting point that foregrounds natural ventilation, thick earthen walls, and the privacy required for Algerian households. As families begin personalizing their plots, small transitional pockets emerge between the communal houma and the enclosed courtyard, while subtle architectural gestures, like low walls or carved openings, announce a growing sense of ownership. By the final phase, certain hwesh have expanded vertically or outward into street-facing shops, reflecting how entrepreneurial activities and household extensions can reshape this urban landscape, one courtyard at a time.

At the Hawsh Scale

— Exterior

Complementing these broader spatial composites are six collages that step into the intimate contours of everyday life. Three of them focus on external domains. One portrays the main courtyard as a site of intersecting paths, where women quietly prepare meals, children spill out in play, and conversation echoes from shaded corners. Another captures the beit el q3ed, an outdoor alcove deliberately set apart so men can gather for a casual chat or tea without intruding on the women’s free movement. The final external collage celebrates the stah, or rooftop terrace, a space that extends the hawsh vertically, transforming laundry tasks or evening get-togethers into moments of communal visibility under the open sky.

At the Hawsh Scale

— Interior

The remaining three collages then move indoors, drawing attention to the hustle of a shared kitchen that becomes a practical and emotional hub for extended families, the hushed intimacy of an in-house hammam adapted to local bathing customs, and the beit el-diaf, or guest room, which remains ready to embrace neighbours and relatives at a moment’s notice. Threaded through each collage are layers of familial memory, cultural nuance, and environmental awareness, revealing how the hawsh model, far from being a static blueprint, becomes a living choreography of domestic routines. By visualizing these spaces in narrative form, the drawings and collages ground the proposed design in the concrete details of Algerian life, offering a more tangible sense of how architecture and culture continuously shape, and reshape, one another.